Two years ago when the blog on “Washington’s Battle with Smallpox” was posted, the struggle was how to convey the fear and anxiety our ancestors experienced as they faced with the smallpox epidemic during the American Revolution. Not only had vaccinations nearly eradicated smallpox, it had been 100 hundred years since the world had faced an epidemic on this scale. Who could imagined that within two years this would all change as our country coped with the greatest pandemic since the Spanish Flu in 1918.

Reminded of the axiom, “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it“,[1] this blog has been revised and updated with information that had been overlooked along with documentation of the ties to additional ancestors. With the hope we can gain a deeper appreciation and understanding, we can look back and learn from the experiences of the Americans as they faced annihilation from smallpox in the early days of the American Revolution. As General Washington demonstrates, it is never too late to change the course and proactively take the “vigorous measures (however disagreeable and inconvenient to Individuals) to remove the Infected and Infection before we feel to sensibly the effects“.

Smallpox in the American Colonies

Smallpox (caused by the Variola major virus) was one of the most feared contagious diseases in the American Colonies. About 12 days after exposure, fever, fatigue, headache, and back-pain were experienced followed by a prominent rash on the face, arms, and legs. From the rash, lesions formed filled with puss that would crust over into scabs that would fall off after a few weeks if the victim survived. Not only did 20-60% of the people (up to 80% of infants) infected die, the faces of survivors were scared with distinctive pockmarks with a third of the survivors left blind.[2] The lone saving grace was that smallpox survivors were immune from contracted the dreaded disease a second time.

In 1721, Boston was enduring a severe outbreak of smallpox when Boston’s influential Reverend Cotton Mather persuaded Dr. Zabdiel Boylston to use a crude method of smallpox inoculation he had learned from an African slave named Onesimus. By making a small incision on a healthy person and introducing an active smallpox lesion taken from someone that had smallpox (living or recently died), a milder case of smallpox generally resulted with significantly higher rates of recovery than people who naturally contracted smallpox. However, while they were sick with the virus the inoculated person was equally capable to transmitting the highly contagious disease if they came in contact with others threatening an outbreak of the virus to the surrounding community.[3]

- Dr. Zabdiel Boylston had been the only member of his family to survive smallpox; and smallpox had killed most of Reverend Cotton Mather’s family.

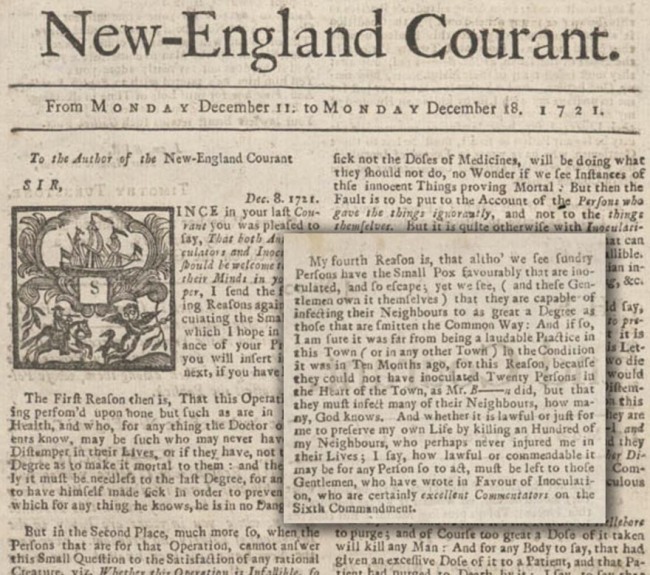

As illustrated by a December issue of the paper printed by James Franklin (older brother of Benjamin Franklin), this early form of inoculation was instantly highly controversial and violently opposed. In addition to claiming smallpox “is a judgment of God on the sins of the people, and to avert it is but to provoke him more” the opponents claimed Dr. Boylston and his supporters “are capable of infecting their Neighbours to as great a Degree as those that are smitten in the Common Way” and questioned “wether it is lawful or just for me to preserve my own Life by killing an Hundred of my Neighbours” suggesting the practice violated the sixth commandment “Thou Shall not kill” (see below). Both Reverend Mather and Dr. Boylston (along with there families) were subjected to attacks by angry violent mobs in opposition of inoculation with crude bomb’s reportedly thrown into both their homes.[4]

The New England Courant dated December 11-18, 1721 (Massachusetts Historical Society).

Instead of embracing Dr. Boylston’s method of inoculation, most of the American colonies enacted strict quarantine laws and notification laws in an effort to prevent smallpox. Apprehension of smallpox inoculations resulted in five colonies (Connecticut, Maryland, New Hampshire, New York, & Virginia) enacting laws prohibiting smallpox inoculations or instituting strict controls over the procedure.[5] Nonetheless, some colonist went against the public sentiment including a 28 year-old John Adams (Dr. Boylston’s nephew) who underwent the procedure in 1764. Although the practice was becoming more commonly accepted, aversions to the practice remained so fierce that in 1774 a hospital on Cat Island (near Salem, Massachusetts) was burned to the ground because “it was feared it would be turned into an inoculating hospital” for smallpox.[6]

Smallpox & the Siege of Boston

After the first shots were fired in Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, the call for aid spread throughout the surrounding colonies as fast as the post riders could ride. The 19 year-old Gurdin Burnham and his two cousins (Augustus Burnham & Aaron Burnham) volunteered in a company of men from Hartford (Connecticut) under the command of Captain George Pitkin. The company of Connecticut volunteers “marched for the relief of Boston” to Roxbury (Massachusetts) to support the siege of the British troops in Boston under the command Lieutenant-General Thomas Gage.[7] After reaching Boston, poor health forced Lieutenant Colonel George Pitkin to returned to Connecticut leaving Lieutenant Colonel/Captain Ozias Bissell in command of the company that was adopted into Continental Army as the 2nd Company, 4th Connecticut Regiment on June 14, 1775.

Gurdin Burnham* was the 4th-Great maternal

Grandfather of William Floyd Wilson

In 1763, General Gage had approved an attempt to infect the waring Indian tribes with smallpox by giving “them two Blankets and an Handkerchief out of the Small Pox Hospital“.[8] Having fought with the British against the Indians, colonist like Seth Pomeroy were well aware of the British willingness to use the deadly and highly contagious smallpox to decimate their enemies.[9] In a letter, Reverend Thomas Allen wrote to fellow Massachusetts militia leader the newly appointed Brigadier General Seth Pomeroy of his concern “General Gage should spread the small-pox” against the Patriot militias surrounding Boston. Pomeroy had known General Gage during campaigns against the French and Indians and echoed his friends concern writing “If it is In General Gages power I Expect he will Send ye Small pox Into ye Army” on May 13, 1775.[10]

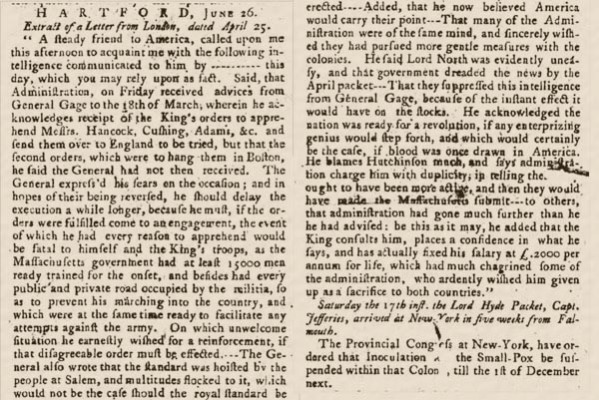

On June 26, 1775, the paper in Hartford (Connecticut) reported the British had issued orders to apprehend and hang the Patriot leaders (including Hancock & Adams) in Boston. Yet, General Gage had reported “at least 15,000” colonial militiamen had “had every public and private road occupied….to prevent his marching into the country” from Boston as the Patriots “were “ready to facilitate any attempts against the army“. Fear of spread of smallpox, the Hartford paper followed the report on Boston with the announcement “the Provincial Congress at New York, have ordered that the Inoculation of the Small-Pox be suspended within the colonies, til the 1st of December next” (see below).[11]

Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut), June 26, 1775, Page 3.

On July 2, 1775, General George Washington arrived at the Patriot encampment in Cambridge (Massachusetts) and assumed control of the forces surrounding the British forces occupying Boston. Washington recognized that smallpox represented as great a threat to his new army as the British. From his encampment at Cambridge, Washington advised John Hancock (President of the Continental Congress) he had “been particularly attentive to the least Symptoms of the small Pox and hitherto we have been so fortunate, as to have every Person removed so soon, as not only to prevent any Communication, but any Alarm or Apprehension it might give in the Camp. We shall continue the utmost Vigilance against this most dangerous Enemy” in a letter dated dated July 21, 1775.[12]

Immune, General Washington had been fortunate to have survived smallpox after contracting the dreaded disease during a trip to Barbados when he was 19 years-old. Personally, Washington was aware of the effectiveness of the smallpox inoculation as his stepson Jack had undergone the procedure in 1771 and his wife Martha would be inoculated in 1776.[13] However, commissioned by the Continental Congress that represented all the colonies left Washington constrained to the anti-inoculation positions adopted by the governing colonial assemblies limiting him to isolating anyone exhibiting symptoms to hospital camps under strict quarantine.

As the Patriots were taking action to address the threat of smallpox, the outbreak of smallpox in Boston was preventing the British from making any additional assaults the American positions after they lost over 1,000 men in the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775. On July 28, Ezekiel Price (Boston Attorney & Suffolk County Clerk of the Court) recorded in his diary that deserters reported the British Regulars had refused to leave Boston to attack the Patriots and the British “Regular Army consists of about six thousand men, and that a great numbers are sick“. He added that “fifteen hundred” of the British Regulars “are unfit for duty” in his diary on August 2, 1775.[14]

- On September 19, 1775, Colonel Benedict Arnold embarked from Cambridge (Massachusetts) with a force of 1,100 men (including the 1st Company, 4th Connecticut Regiment) to support Brigadier General Richard Montgomery in the evasion of Canada.

General Gage was recalled to Great Britain and General William Howe assumed command of the British forces in Boston on October 1, 1775. With “the smallpox being likely to spread“, in November General Howe issued orders to have British Regulars in Boston “Enoculated as have not had it as soon as possible“. On December 1, 1775, British orders stipulated “the Small Pox spreading universally about the Town, makes it necessary for the safety of the Troops, that such men as are willing, and have not had that distemper shou’d be inoculated immediately“.[15]

On November 27, 1775, General Washington advised Colonel Joseph Reed of his surprise that the British did not take any action against the Americans “taking possession of Cobble Hill“. Washington added that “By order of Genl. Howe, 300 of the poor Inhabitants of Boston were landed on Saturday last at point Shirley… Yesterday in the evening I received information that one of them was dead, & two more expiring“. He concluded that he was “under dreadful apprehensions of their communicating the small Pox as it is Rief in Boston” and that he had “forbid any of them coming to this place on that acct“.[16]

- In November, the American forces under Colonel Benedict Arnold arrived in Quebec and soon thereafter there were outbreaks smallpox. The British governor, General Guy Carleton, was reported to have sent the smallpox out to the Americans by “inoculating the poor people at government expense for the purpose of giving it to” their army.[17] One of the young Patriots in Colonel Arnold’s command, John Joseph Hill, noted this was done by sending “a number of women loaded with the infection of the small-pox, came into” the Americans encampment.[18]

On December 4, 1775, General Washington advised John Hancock that the British in Boston were “goeing to Send out a number of the Inhabitants in order it is thought to make more room for his expected reinforcements” and that “a number of these Comeing out have been innoculated, with design of Spreading the Smallpox thro’ this Country & Camp“.[19] On December 14, 1775, Washington advised Hancock “about 150 more of the poor Inhabitants are come out of Boston, the small pox rages all over the Town, such of the Military as had it not before, are now under inoculation. This I apprehend is a weapon of defence, they are using against us…“.[20] This was apparently confirmed by Price as he recorded that Mrs. Sutton reported “the people who came out last from Boston, and landed at Point Shirley, have the small-pox among them there“. She added “Dr. Rand of Boston had said that he had effectually given that distemper among those people“, suggesting he had inoculated them with smallpox before they had departed from Boston.[21]

When his enlistment ended on December 10, 1775, Gurdin Burnham* reports that he enlisted for an additional 12 months under Captain Holdridge and was then placed under the command of Colonel Wyllys. Captain Hezekiah Holdridge commanded a company (22nd Continental) that had been reorganized following the end of their enlistments and was placed under the command of Colonel Samuel Wyllys and Lieutenant Colonel Rufus Putnam.[22] On December 15, General Washington wrote “the smallpox is in every part of Boston. The soldiers there who have never had it, are, we are told, under innoculation, and considered as a security against any attempt of ours. A third shipload of people is come out to Point Shirley. If we escape the smallpox in this camp, and the country around about, it will be miraculous. Every precaution that can be is taken, to guard against this evil, both by the General Court and myself.“[23]

- By December 31, 1775, the outbreaks of smallpox and impending expirations of enlistments compelled the Americans to make an ill-fated assault the British in Quebec. General Montgomery was one of the 50 Americans killed, 34 Americans (including Colonel Arnold) were wounded, and 431 Americans (including Colonel Daniel Morgan) were captured. Though wounded, Colonel Arnold was able to maintain an ineffective siege of Quebec with the remaining 800 American troops.

- Major Lockwood later reported to the congressional committee investigating the invasion’s failure that “when Montgomery made the attack there were 2 or 300

sick” with “not above 800 men fit for duty.“ (need citation)

During the next two months, the stalemate continued as General Howe appear confident the Americans could not continue to sustain their positions due to the lack of supplies, the toll of diseases such as smallpox, and the belief many of the men would need to return home to plant their spring crops. Although smallpox continued to be a problem, General Washington continued to remove anyone contracting the disease to hospital camps in which they were under strict quarantine. Washington made use of this stalemate by sending Colonel Henry Knox to retrieve the heavy pieces of artillery that had been captured from the British at Fort Ticonderoga.

After General Washington was able to fortify Dorchester Heights with cannons moved from Fort Ticonderoga, the British were compelled to abandon Boston on March 17, 1776. On March 19, 1776, General Washington advised the Continental Congress that he had “ordered a thousand men (who had had the smallpox), under command of General Putnam, to take possession of the heights” of Boston following the British evacuation.[24] According to Gurdin Burnham*, he was among the troops that marched into Boston after the evacuation by the British suggesting he had survived smallpox prior to his enlistment or sometime during the siege.[25]

New York Campaign & Destruction of the Northern Army by Smallpox

After their evacuation of Boston, General Washington was convinced the British would move their forces to occupy New York. On April 29, 1776, from New York Washington advised his brother that he had “brought the whole Army which I had in the New England Governments (five Regiments excepted, & left behind for the defence of Boston and the Stores we have there) to this place; and Eight days ago, Detached four Regiments for Canada; and am now Imbarking Six more for the same place“. Washington also noted that in New York “there are too many inimical persons” obstructing the cause. On April 17, Washington had requested the New York Committee of Safety to put and end to any future support of the British.[26]

On May 4, 1776, Gurdin Burnham* reports his company of Connecticut Continentals landed in New York where they set about building Fort Washington.[27] To replace the men sent to Canada, new troops enlist from the other colonies were sent to New York. This is known to have included Samuel DeWees (1715-1777) and his two oldest sons (John & William) along with his wife Elizabeth from (Pennsylvania); and Robert McCready from (Maryland).

Samuel DeWees was the 5th-Great paternal

Grand Uncle of Eula Claudine Reed

Robert McCready was the 3rd-Great maternal

Grand Uncle of Eula Claudine Reed

On May 8, 1776, from Montreal (Canada) Brigadier General Benedict Arnold reported to General Washington that “Our Army Consists of few more than Two thousand Effective Men, & twelve hundred sick & unfit for duty chiefly with the small Pox which is universal in the Country“.[28] On the same day, the report to Washington from Major General John Thomas in Quebec was even grimmer stating of the 1,900 men “only a 1000 were fit for duty, Officers included; the remainder were Invalids, chiefly confined with the small pox” with “three hundred of the effective were Soldiers whose inlistments expired…many of whom peremptorily refused duty, and all were very importunate to return home; and two hundred others engaged for the year, had received the infection of the small pox by inoculation, & wou’d in a short time be in the Hospitals“. Consequently, “not more than 300 men could be rallied to the relief of any one post, should it be attacked by the whole force of the enemy“.[29]

- A short time after he arrived to assume command (May 1, 1776), the 52 year-old Major General John Thomas contracted smallpox and died during the retreat on June 2, 1776.

On May 24, 1776, Doctor Foster appeared before the General Committee of the Provincial Congress of New York with information “that Lt Colonel Moulton, Capt. Parks, Doctor Hart and Lieut. Brown had been inoculated by Doctor Azor Betts“. A British sympathizer, Dr. Azor Betts had previously detained by local officials and prevailed to be pardoned by the committee. Dr. Betts appeared before the committee and claimed “he had been repeatedly applied to by the officers of the Continental Army to inoculate them, that he refused, but being overpersuaded, he at last inoculated” them. Moreover, additional information from his wife indicated seven other officers had been, or were preparing to be, inoculated by Dr. Betts. As a result, Dr. Betts was placed in the custody of the Provincial Congress and a report was sent to Major General Putnam “that he may give such directions to the Continental army for preventing the small pox among them on Long Island“.[30]

On May 26, 1776, General Orders issued from General Washington stated “The General presents his Compliments to the Honorable The Provincial Congress, and General Committee, is much obliged to them, for their care, in endeavouring to prevent the spreading of the Small-pox (by Inoculation or any other way) in this City, or in the Continental Army, which might prove fatal to the army, if allowed of, at this critical time, when there is reason to expect they may soon be called to action; and orders that the Officers take the strictest care, to examine into the state of their respective Corps, and thereby prevent Inoculation amongst them; which, if any Soldier should presume upon, he must expect the severest punishment….Any Officer in the Continental Army, who shall suffer himself to be inoculated, will be cashiered and turned out of the army, and have his name published in the News papers throughout the Continent, as an Enemy and Traitor to his country.“A similar order had been issued six days earlier “as it is at present of the utmost importance that the spreading of that distemper, in the Army and City, should be prevented“.[31] A corresponding report “against Inoculation for Small Pox” was submitted to the Provisional Congress in New York by James Livingston recognizing “…the dangerous consequences of the small pox spreading in this Colony. (Especially as great numbers of the Army have not had it) to prevent the same as much as Possible we do resolve that no Doctor or any other Person.. whatsoever do presume at any time or times hereafter to inoculate any person of persons with the Small Pox within this Colony…” on June 1, 1776.[32]

In a letter dated May 31-June 4, 1776, General Washington (from Philadelphia) notified his brother John Augustine Washington “Mrs Washington is now under Innoculation in this City; & will, I expect, have the Small pox favourably—this is the 13th day, and she has very few Pustules—she would have wrote to my Sister but thought it prudent not to do so, notwithstanding there could be but little danger in conveying the Infection in this Manner“.[33] Bills paid by Mrs. Washington suggest Dr. William Shippen Jr. (Chief Physician & Director General of the Hospital of the Continental Army in New Jersey) had administer the inoculation procedure on Mrs. Washington and oversaw her for the sum of £13.

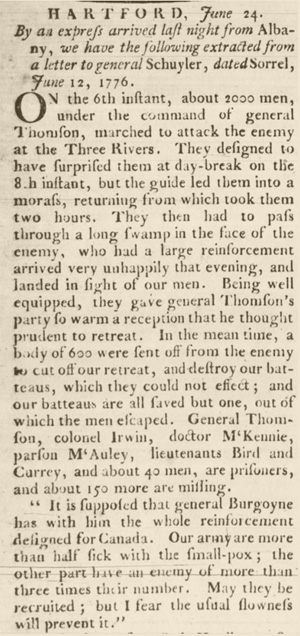

On June 13, 1776, General Washington (from New York) notified Brigadier General Sullivan that “Having received intelligence of the unfortunate death of General Thomas, occasioned by the smallpox he had taken, the command of the army in Canada devolves on you. I am therefore to request your most strenuous exertions to retrieve our circumstances in that quarter from the melancholy situation, they are now in, and for performing the arduous task of bringing order out of confusion“.[34] On June 24, orders were issued by Washington for Major General Horatio Gates to assume command in Canada. From the Continental Congress John Adams confided to his wife Abigail “Our Misfortunes in Canada, are enough to melt an Heart of Stone. The Small Pox is ten times more terrible than Britons, Canadians and Indians together. This was the Cause of our precipitate Retreat from Quebec, this the Cause of our Disgraces…“. He added “I could almost wish that an innoculating Hospital was opened, in every Town in New England“, on June 26, 1776.[35]

On the same day the Continental Congress approve the Declaration of Independence (July 4, 1776), Connecticut Governor Jonathan Trumbull advised General Washington “the retreat of the northern army and its present situation, have spread a general alarm. The prevalence of the smallpox among the troops is every way unhappy. Our people in general have not had that distemper. Fear of the infection operates strongly to prevent soldiers from engaging in the service.” On July 7, 1776, Washington responded to Governor Trumbull “the Situation of the Northern Army is certainly Distressing but no Relief can be afforded by me…if proper precautions are taken, the small pox may be prevented from spreading—this was done at Cambridge and I trust will be contrived by Generals Schuyler and Gates, who are well Apprized of fatal Consequences that may Attend its infecting the whole Army…”.[36]

Purdie’s Virginia Gazette (Williamsburg, Virginia) dated July 12, 1776, Page 2.

On July 16, 1776, Major General Horatio Gates reported to Hancock after arriving in Canada that he “…went with General Schuyler, and General Arnold, to Crown-point, where we found the wretched remains of what was once a very respectable Body of Troops. That pestilential disease, the Small pox, had taken so deep a root, that the Camp had more the Appearance of a General Hospital, than an Army form’d to Oppose the Invasion of a Successful & enterprizing Enemy.” On the same date Gates reported to Washington that “since the beginning of May, the Losses sustain’d by the Enemy, Death & Desertion, amounts to more than Five Thousand Men, and to this must be added, three Thousand that are now Sick“. On July 29, 1776, Gates reported to Washington that “every thing about this Army is infected with the Pestilence; The Cloaths, The Blanketts, The Air, & the Ground they Walk upon; to put this Evil from us, a General Hospital is Established at Fort George, where there are now between Two, & Three Thousand Sick, & where every Infected Person is immediately sent; but this Care and Caution has not yet effectually destroyed the Disease here“.[37]

On August 7, 1776, Major General General Horatio Gates informed General Washington “the very great desertion rate from this Army has, I believe, been principally occasioned by the dread of the smallpox“. Gates added “Justly Captain Weatherbee deserves to be punished—These Men get an Enormous Bounty from their Countrymen, are Highly paid by the Continent, & then rather than March where they are commanded, they get inoculated, by which, a Month of the short Time they are engaged for, Elapses, & perhaps the Health of the whole Army is Endang(ered)“.[38]

- In Charlestown (New Hampshire), about twenty-five men in Captain Samuel Wetherbee’s company were inoculated for smallpox before the doctor learned of the general orders forbidding the inoculation of troops.

By August, the British had arrived in New York with a reinforced army of about 22,000 men (including 9,000 Hessians) with naval support. After the failed attempt to destroy a British squadron with fireships in which Gurdin Burnham* was severely burned (see Gurdin Burnham’s Suicide Mission), the British defeated Washington at the Battle of Long Island on August 27, 1776. General Washington was able to save his army by evacuating to Manhattan and then moving north to White Plains (New York) where he was again able to evade capture following an engagement (Battle of White Plains) on October 28, 1776. However, the American forces that remained on the northern end of Manhattan Island at Fort Washington (including Samuel DeWees) failed to evacuate and were captured on November 16, 1776.

- On September 3, 1776, the 6th Virginia Regiment (including James Madison Crews* & his brother Gideon Crews) was transferred from the Southern Division of Continental Army to the main army under General Washington and participated in engagements at Chesapeake Bay and Northern New Jersey.[39] Combined with the 4th and 5th Virginia Regiments, the 6th Virginia Regiment was part of “Stephen’s Brigade” under the command of the 5th Virginia’s Colonel Charles Scott.[40]

James Madison Crews* was the 4th-Great maternal

Grandfather of William Floyd Wilson

After he was captured, Samuel DeWees (1715-1777) was sent to a prison ship by the British off the shores of Brooklyn (New York) where his wife Elizabeth plead with the British to allow her to board the ship to give aide to her husband and “after repeated importunities her request was at length granted“. Elizabeth DeWees quickly succumbed to the sickness (possibly smallpox) “owing to the great pestilential stench created by so many sick and wounded soldiers being huddled together” in the confined space of the prison ship. Desperately ill, Elizabeth DeWees “begged so hard” the British officers relented and released her and Samuel DeWees (1715-1777) “upon parole of honor…that he would not be found bearing arms thereafter against Great Britain” with the hope of spreading the disease to the Americans. After their release, they recovered and made their way to Philadelphia (Pennsylvania) were Elizabeth DeWees died after she had “taken ill again“.[41]

- It is estimated that as many as 11,000 American colonist died onboard British prison ships from disease (including smallpox) or malnutrition during the Revolutionary War. This was more than double the number of American soldiers believed to have been killed (around 4,500) in armed combat with the British.

By December, General Washington and what remained of his army had evade the capture by crossing the Delaware River into Pennsylvania. With low moral and enlistments set to expire, with 2,400 troops (10% of the troops he had in New York) remaining in his army Washington surprised the British by crossing the Delaware River and capturing the British (Hessian) at Trenton (December 26, 1776) and defeating the British at Princeton (January 3, 1777). The British forces were forced to withdraw back to New York City with with posts stretching down to New Brunswick (New Jersey) for the winter allowing General Washington to set up camp in Morristown (New Jersey) to rebuild his army.

- Protected by the Watchnung Mountians, Morristown (New Jersey) was strategically located about 30 miles west of the British encampments in New York City and 30 miles north of the British encampment in New Brunswick (New Jersey).

The Forage War & Smallpox Inoculation

After months the defensive reacting to the attacks of the British and smallpox, General Washington had saved his army and the revolution with his audacious attacks at Trenton and Princeton. With his army decimated due to the casualties from disease and the British along with expired enlistments, Washington need time to rebuild his army. To conceal his weakened army from the British, Washington ordered detachments to proactively harass the British forages for supplies along their outlying posts which inflicted more British casualties than the entire New York Campaign and would be known as the Forge War or “petit guerre“.

- The 6th Virginia Regiment (including James Madison Crews & his brother Gideon Crews) supported Colonel Daniel Morgan’s Provisional Rifle Corps to conduct operations against the outlying British (less than 30 miles south of Morristown) posts near Brunswick, New Jersey. Utilizing remarkable marksmanship, they were able to snipe at the British from a distance, masked the numbers of Continental troops engaged while limiting their exposure to hostile fire from the British.

While the British were harassed, General Washington sought to take proactive steps to eliminate smallpox from his army. To gain the support of the Continental Congress to override the prohibition on smallpox inoculations in the colonies, General Washington (from Morristown) authorized his aide-de camp Lieutenant Colonel Robert Hanson Harrison (in Philadelphia) “to consult, and in my name advise and direct such measures as shall appear most effectual to stop the progress of the Small pox; when I recall to mind the unhappy situation of our Northern Army last year I shudder at the consequence of the disorder if some vigorous steps are not taken to stop the spreading of it. Vigorous measures must be adopted (however disagreeable and inconvenient to Individuals) to remove the Infected and Infection before we feel too sensibly the effects.” Washington added “Doctr Cockran will set out tomorrow for New Town & will assist you in the Matters before mentioned relative to the Small pox people” on January 20, 1777.[42] Lieutenant Colonel Robert Hanson Harrison had reportedly gone to Philadelphia to be inoculated for smallpox himself and had recovered sufficiently to solicit support of inoculation from the Continental Congress.

On January 10, 1777, the 6th Virginia Regiment (including James Madison Crews & his brother Gideon Crews) along with the 4th & 5th Virginia under Colonel Charles Scott captured a British foraging party of seventy Highlanders with “a large number of baggage wagons“. On January 16, 1777, it is likely the 6th Virginia Regiment were part of the force that attacked a British foraging party near Bonhamtown (near New Brunswick) that killed 21 British troops and wounded 30-40 more The 6th Virginia Regiment (including James Madison Crews & his brother Gideon Crews) would again be involved in the route of two British regiments by New Jersey militia outside of Woodbridge (near New Brunswick) on January 23, 1777 (see Washington’s report to Hancock on January 26).[43]

- Captain Alexander Lawson Smith (4th Regiment, 2nd Maryland Brigade) described the skirmishes in a letter on February 17, 1777, “…we have had scouting Parties out ever since the Enemy Retreated to Brunswick & has Harrassed them very much we have had severall Skirmishes with them & I Cant say but we have been Successful in each Skirmish tho we have been obliged to give way to the Supearer force…on the 23d of Jan. Commanded 4 by Col Parker from Virginia which lasted upwards of twenty Minutes we did not lose one man, from Accst of the Neighbors where the Ingagement was do say that the Enemy lost upwards of thirty men Killed & many wounded...”[44]

On January 20, 1777, General Washington ordered Doctor John Cochran “to proceed from hence to New Town, to morrow & there inquire into the state of the smallpox & use every possible Means in your Power to prevent that Disease from spreading in the Army & among the Inhabitants, which may otherwise prove fatal to the service; To that End you are to take such Houses, as will be convenient in the most retired parts of the Country & best calculated to answer that Purpose. You will then proceed to Philadelphia & consult Doctor Shippen the Director about forming an Hospital for the ensuing Campaign, in such Manner as that the sick & wounded may be taken the best Care of & the inconveniencies in that Department, so much complained of, the last Campaign, may be remedied in future. You will also in Conjunction, with Doctor Shippen, point out to me, in writing, such officers & stores as you may think Necessary for the Arrangement of an Hospital, in every Branch of the Department as well to constitute One for an Army in the field, which may be stiled a flying Hospital, as also, fixed Hospitals in such parts of the Country as the Nature of the service, from time to time may require“.[45]

Lieutenant Colonel Robert Hanson Harrison found support from members of the Continental Congress to take new aggressive measures to eliminate smallpox from the army. On January 25, 1777, Doctor William Shippen (from Philadelphia) advised General Washington “the smallpox rases & it is the opinion of the committee of Congress & the generals that inoculation should take place immediately in such a manner as that those who pass & repass hereafter, may not be liable to recieve the infection unless circumstances may make it proper. It is 3 to 1 that all in town have taken the infection & will carry it to the Army unless inoculated“.[46]

On January 26, 1777, General Washington (from Morristown) reported to John Hancock included a brief summary of an engagement on January 23 by the 6th Virginia Regiment (including James Madison Crews* & Gideon Crews) in which “a party of 400 of our Men under Colo. Buckner fell in with two Regiments of the Enemy, conveying a Number of Waggons from Brunswic to Amboy. Our advanced party under Colo. parker engaged them with great Bravery upwards of twenty Minutes, during which time, the Colo. Commandant was killed and the second in command mortally wounded. The people, living near the Feild of Action, say, their killed and wounded were considerable. We lost only two Men who were made prisoners. Had Colo. Buckner come up with the main Body, Colo. parker and the other Officers think we should have put them to the rout, as their confusion was very great and their ground disadvantagious. I have ordered Buckner under Arrest, and shall bring him to tryal, to answer so extraordinary a peice of Conduct.” Washington added that “reinforcements come up so extremely slow, that I am afraid I shall be left without any Men, before they arrive. The Enemy must be ignorant of our Numbers, or they have not Horses to move their Artillery, or they would not suffer us to remain undisturbed. I have repeatedly wrote to all the recruiting Officers to forward on their Men as fast as they could arm and cloath them…It would be well, if the Board of War, in whose department it is, would issue orders for all Officers to equip and forward their Recruits to Head Quarters with the greatest Expedition“.[47]

- On February 8, 1777, Colonel Mordecai Buckner was convicted at his court-martial of cowardice for fleeing from his command after General Washington refused to accept his letter of resignation and nearly executed before he was allowed to leave the army.[48] Major James Hendricks was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel to command the 6th Virginia Regiment.

Having gain the support from the Continental Congress, General Washington informed the Continental Congress “the smallpox has made such Headway in every quarter that I find it impossible to keep it from spreading throughout the Army, in the natural way. I have therefore, determined not only to inoculate all the troops now here, that have not had it, but shall order Doctor Shippen to inoculate the Recruits as fast as they come into Philadelphia” on February 5, 1777.[49]

Having made the decision to inoculate his army in the field, General Washington recognized the peril the army would be in if the British realized the weakened condition of his army and attacking while the troops were still recovering from the smallpox. To gain the support of Major General Horatio Gates, General Washington appealed to Gate ego by advising him “I am much at a loss what Step to take to prevent the spreading of the smallpox; should We innoculate generally, the Enemy, knowing it, will certainly take Advantage of our Situation; ’Till some good Mode can be adopted, I know of no better than to alter the Route of the Troops marching from the South; You will therefore command all such to pass by the way of Newtown, and not to touch at Philada under the most certain and severe Penalty—To accomodate them whilst at Newtown, I would have an Issuing Store instantly established there; and likewise an Officer of some distinction quartered there, whose business shall be to receive & forward them. If it can be made convenient to Colo. Dehaas, I wish he could be appointed to this duty” in a letter dated February 5-6, 1777.[50]

On February 6, 1777, General Washington informed William Shippen Jr “Finding the Small pox to be spreading much and fearing that no precaution can prevent it from running through the whole of our Army, I have determined that the troops shall be inoculated. This Expedient may be attended with some inconveniences and some disadvantages, but yet I trust in its consequences will have the most happy effects. Necessity not only authorizes but seems to require the measure, for should the disorder infect the Army in the natural way and rage with its usual virulence we should have more to dread from it than from the Sword of the Enemy. Under these circumstances I have directed Doctr Bond to prepare immediately for inoculating in this Quarter, keeping the matter as secret as possible, and request that you will without delay inoculate All the Continental Troops that are in philadelphia and those that shall come in as fast as they arrive. You will spare no pains to carry them through the disorder with the utmost expedition, and to have them cleansed from the infection when recovered, that they may proceed to Camp with as little injury as possible to the Country through which they pass. If the business is immediately begun and favoured with the common success, I would fain hope they will be soon fit for duty, and that in a short space of time we shall have an Army not subject to this the greatest of all calamities that can befall it when taken in the natural way“.[51]

General Washington continued to be advised the British were attempting to spread smallpox to the Americans when Connecticut Governor Turnbull reported to him “…but cannot say very nearly, the small Pox is spreading in many Towns comunicated by our cruel Enemies to the Prisoners They have lately sent out & by them thro the Country, which is an additional delay to the recruiting Service” on February 7, 1777. On February 10, 1777, Washing responded to Turnbull “the impossibility of keeping the Small Pox from spreading through the Army in the natural way, has determined us, upon the most mature deliberation, to innoculate all the new Troops that have not had this disorder—I have wrote to General Parsons to fix upon some proper place, and to superintend the innoculation of the Troops of your State, taking it for granted, that you would have no objection to so salutary a measure, upon which depends not only the lives of all the men who have not had the small pox, but also the health of the whole Army, which would otherwise soon become a Hospital of the most loathsome kind—Proper steps are taking to innoculate the Troops already here, and all the Southern Levies will undergo the operation as they pass Philadelphia.” Washington added “I have wrote to the States of New York and Rhode Island to have their Troops also innoculated, and I hope our Army will, by these precautions, be entirely free of that terrible disorder the ensuing Campaign—“.[52]

Members of the Continental Congress remained apprehensive of the decision to inoculate the troops and expressed their desire to have General Washington to take sole responsibility for controversial decision. On February 13, 1777, Dr. Benjamin Rush of the Continental Congress Medical Committee advised General Washington “Apprehending that the Small Pox may greatly endanger the Lives of our fellow Citizens who Compose the army” the Congress had “directed their Medical Committee to request your Excellency to give Orders that all who have not had that Disease may be Inoculated“. The committee also wanted to remind Washington “that the Southern Troops are greatly Alarmed at the Small Pox, and that it very often proves fatal to them in the Natural way“.[53]

With the plan of having troops free of smallpox and ready for the summer campaign against the British, General Washington quickly organized and implemented the mass inoculation of the men who had never had smallpox (estimated 75%) as he tried to rebuild his army. This was done by dispatching doctors to the surrounding camps and separating the men to be inoculated to guarded isolated private homes and churches in the nearby villages (Whippany & Mendam) that were set up as temporary Smallpox inoculation hospitals. The troops were sent en masse at five-to-six day intervals with most recovering within two-three weeks.[54] Captain Alexander Lawson Smith (4th Regiment, 2nd Maryland Brigade) reported in a letter dated February 17, 1777, “…all our Regiment that has not had the Small Pox marched up hear to Whipiney to be Enoculated, this is a small Town about five miles Distant from Morrice Town…“.[55]

- By mid-March, there were only 2,500 Continental troops with General Washington.[56]

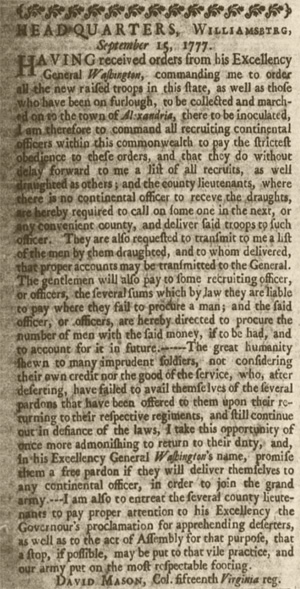

On March 29, 1777, Virginia Governor Patrick Henry advised General Washington that “the recruitting Business of late goes on so badly, that there remains but little prospect of filling the six new Battalions from this State voted by the Assembly. the Board of Council see this with great Concern; and after much Reflection on the Subject, are of Opinion, that the Deficiency in our Regulars, can no Way be supply’d so properly, as by inlisting Volunteers…I beleive you can receive no assistance by Draughts from the Militia. From the Battalions of the Commonwealth, none can be drawn as yet, because they are not half full.” Henry added “Virginia will find some Apology with you for this Deficiency in her Quota of Regulars…The Terrors of the small pox, & the many Deaths occasion’d by it, and the Deficient Inlistments are accounted for in the best Manner I can.”[57] Washington expressed his frustration that Virginia still did not permit the inoculation of smallpox when he responded “the Apologies you offer for your deficiency of Troops are not without some Weight. I am induced to beleive, that the apprehensions of the Small pox & its calamitous consequences, have greatly retarded the Inlistments; but may not those Objections be easily done away by introducing Innoculation into the State—Or shall we adhere to a regulation preventing it, reprobated at this time not only by the consent & usage of the greater part of the civilized World but by our Interest & own experience of its Utility? You will pardon my Observations upon the Small pox, because I know it is more destructive to an Army in the Natural way, than the Enemy’s Sword, and because I shudder when ever I reflect upon the difficulties of keeping it out, and that in the vicissitudes of War, the Scene may be transferred to some Southern State should it not be the case their Quota of Men must come to the Feild” on April 13, 1777 (Virginia rescinded the restriction by April 23, 1777).[58]

On April 12, 1777, from “near Bonam Town” (Bonhamtown, New Jersey) Lieutenant Colonel James Hendricks reported to General Washington that his regiment (6th Virginia) had been “order’d on detachment, with part of 1st 3rd 4th 5th 6th Virga and Colo. Rallings’s regiment, (with which I am now Station’d on the lines) all of which appears to me in as Miserable a Condition (and Some worse) than the 6th Regt…The Sixth regt are now at Whippany, Chatham, New Ark, Elizabeth Town, Pesaick“. Hendricks added “the Sixth regt are barer and unfitter to take the field than others, I can assure you (and wou’d wish to have the matter Enquired into) that I can produce more men and in as good order than the 1st 3d 4th or 5th Virga regiments“.[59] Bonhamtown was a fortification statically located near the British garrisons in New Brunswick and Staten Island (New York).

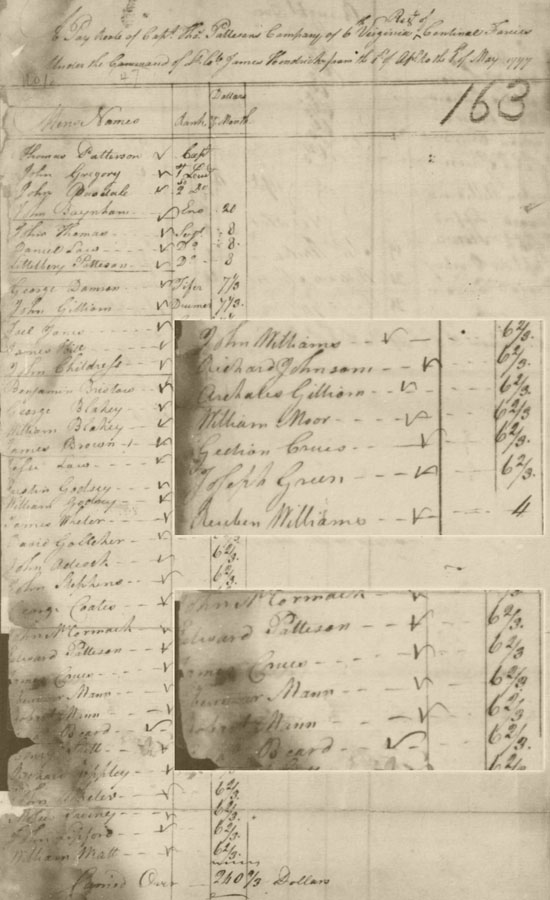

- Privates James Crews* and Gedion Crews were both listed on the “Payroll of Captain Thos Patterson’s Company of the 6th Virginia Regiment…under the command of Lt. Col. Hendricks from the 1st of April to the 1st of May”.[60]

Copies from the Payroll of Captain Thomas Patterson’s Company of the 6th Virginia Regiment (National Archives, ID #602384, NARA M236, Roll 0103).

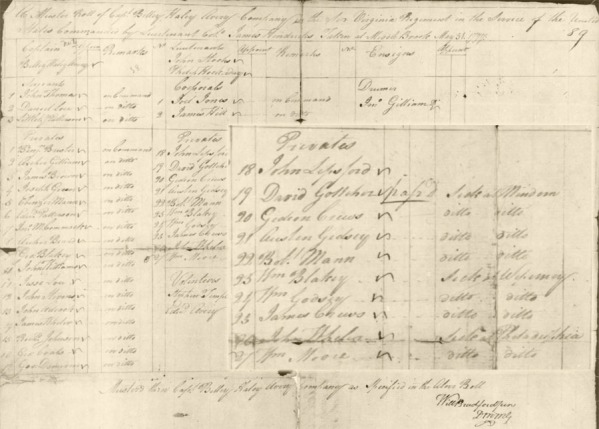

General Washington had reorganized his forces and relocated his troops from Morristown to the Middle Brook encampment along the ridge of First Watchung Mountain by May 31, 1777. James Crews* and his brother Gideon Crews were some of the last men pulled from the frontlines to be inoculated for smallpox. By the end of May, both had been transferred over to the company of Captain Billey Haley Avery after Captain Thomas Patterson (and likely his lieutenant) died of small pox demonstrating the peril of the procedure. On May 31, 1777, Captain Avery’s Company was with General Washington at Middle Brook. However, private James Crews* was “sick at Whipany” along with two other privates; and Gideon Crews was “sick at Mendam” along with three other privates; indicating both were still recovering from inoculation for smallpox (see below).[61]

- Listed as “sick at Philadelphia”, private William Moore confirmed he “was inoculated with the Small pox and wintered at Wilmington in the Spring following being 1777”.[62]

Copies from the Muster Roll of Captain Billey Haley Avery’s Company of the 6th Virginia Regiment (National Archives, ID #602384, NARA M246, Roll 0103).

On May 2, 1777, a report from a committee of the Continental Congress reported “The Enemy wearied and disappointed in their Winter’s Campaign still continue in a State of Dormancy at New York and Brunswick…Our Troops have been under inoculation for the Small Pox with great Success, which Purgation we hope will be a Means of preserving them from fevers in the Summer, however, it will frustrate one Cannibal Scheme of our Enemies who have constantly fought us with that disease by introducing it among our Troops.“[63]

On June 17, 1777, General Washington (from Middle Brook) indicated the mass inoculation of his army had been completed when he advised Major General Israel Putnam “You have done well in sending on the Troops though they have not had the small pox. The Camp is thought to be entirely clear of infection & the Country pretty much also. If it is not, Innoculation may be carried on, should it be found expedient“.[64] The audacious decision to force the colonies to change the laws as Washington ordered the inoculated his entire army while facing a vastly superior British force encamped within 30 miles had been done in secret with the death of only four in every 500 men inoculated (well less than 1% mortality).[65] In 1781, Dr. Benjamin Rush (Surgeon General to the Continental Army and signer of the Declaration of Independence) professed “the small-pox which once proved equally fatal to thousands, has been checked in its career, and in a great degree subdued by the practice of inoculation“.[66]

- General Washington would continue to have new recruits inoculated during the remained of the war. After he rejoined the main army under General Washington, sometime around “October or November 1777” Samuel DeWees (1715-1777) “was sent to take charge” of soldiers sick with smallpox at an encampment near Allentown (aka: Northampton Town) in Bucks County (Pennsylvania) where he had his son Samuel DeWees (Jr) “inoculated with the real small-pox”. Samuel DeWees (1715-1777) would remained at the hospital until his death from a fever around the end of the year.[67]

Purdie’s Virginia Gazette (Williamsburg, Virginia) dated September 19, 1777, Page 2.

As he nearly eliminated the threat of smallpox to his army, General Washington had assembled on of the elite fighting forces of the war. The riflemen of the 6th Virginia Regiment (including James Crews* & his brother Gideon Crews) would be assigned to Colonel Daniel Morgan to form one of the first “special forces” of 500 riflemen (Morgan’s Riflemen) selected from Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia regiments of the Continental Army. Formally placed under the command of Colonel Morgan on June 13, 1777, this elite unit of marksman would prove pivotal in the defeat of the British at Sarasota in September 1777 that convinced the French to sign a formal reliance with our new democracy.

Winston Churchill ounce said “Success is never found. Failure is never fatal. Courage is the only thing“. In 1776 and 1777, General Washington proved his failures were not fatal by having the courage to learn from them. Washington avoid the trap of stubborn arrogance of continuing the make the same mistakes over and over again. Instead, Washington demonstrated remarkable courage and resolve to boldly change course, creating a new opportunity which earned him the success for which he is now remembered.

God Bless!

[1] The Life of Reason: Reason in Common Sense by George Santayana, 1905 (Philosopher, poet, literary and cultural critic, George Santayana is a principal figure in Classical American Philosophy – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

[2] “Edward Jenner and the History of Smallpox and Vaccination” by Stephan Riedel, MD, PHD (Baylor University Medical Center).

[3] Smallpox at the Siege of Boston: “Vigilance against this most dangerous Enemy” by Ann M. Becker, Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Volume 45 (1), Winter 2017, Page 45.

[4] The Speckeld Monster: A Historical Tale of Battling SmallPox by Jennifer Lee Carrell, Page 439-440.

[5] “Smallpox in Washington’s Army: Strategic Implications of the Disease During the American Revolutionary War” by Ann M. Becker, The Journal of Military History (Volume 68, No. 2), Pages 387-388.

[6] A Short History of the English Colonies in America by Henry Cabot Lodge, Pages 420-421.

[7] Record of Service of Connecticut Men, edited by Henry P. Johnston A.M, Hartford, 1889, Pages 13 & 59.

[8] “The British, the Indians, and Smallpox: What Actually Happened at Fort Pitt in 1763?” by Philip Ranlet, Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies (Volume 67, No. 3), Pages 427-441; Smallpox at the Siege of Boston: “Vigilance against this most dangerous Enemy” by Ann M. Becker, Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Volume 45 (1), Winter 2017, Pages 50-51.

[9] Smallpox at the Siege of Boston: “Vigilance against this most dangerous Enemy” by Ann M. Becker, Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Volume 45 (1), Winter 2017, Pages 49-52.

[10] The Journals and Papers of Seth Pomeroy: Sometime General in the Colonial Service edited by Louis Effingham DeForest, Pages 166-167; History of the Siege of Boston by Richard Frothingham, Page 214.

[11] Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut), June 26, 1775, Page 3.

[12] Letter from General George Washington to John Hancock dated July 21, 1775 (National Archives).

[13] “Smallpox in Washington’s Army: Strategic Implications of the Disease During the American Revolutionary War” by Ann M. Becker, The Journal of Military History (Volume 68, No. 2), Page 390.

[14] “Diary of Ezekiel Price, 1775-6” by Ezekiel Price, Proceedings of the Massachusetts

Historical Society, Volume 7 (November 1863), Pages 200-202.

[15] Smallpox at the Siege of Boston: “Vigilance against this most dangerous Enemy” by Ann M. Becker, Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Volume 45 (1), Winter 2017, Page 58.

[16] Letter from General George Washington to Joseph Reed dated November 27, 1775 (National Archives).

[17] “Smallpox in Washington’s Army: Strategic Implications of the Disease During the American Revolutionary War” by Ann M. Becker, The Journal of Military History (Volume 68, No. 2), Pages 408-409.

[18] Journal of the Campaign Against Quebec by John Joseph Henry, Page 131.

[19] Letter from General George Washington to John Hancock dated December 4, 1775 (National Archives).

[20] Letter from General George Washington to John Hancock dated December 14, 1775 (National Archives).

[21] “Diary of Ezekiel Price, 1775-6” by Ezekiel Price, Proceedings of the Massachusetts

Historical Society, Volume 7 (November 1863), Pages 220.

[22] Revolutionary War pension application of Gurdin Burnham dated June 3, 1833 (National Archives, ID #300022, NARA M804, Roll 0420); The Record of Connecticut Men in the Military and Naval Service during the War of the Revolutions (1775-1783) edited by Henry P. Johnston, Page 107.

[23] Letter from General George Washington to Joseph Reed dated December 15, 1775 (National Archives).

[24] Letter from General George Washington to Continental Congress dated March 19, 1776 (National Archives).

[25] Revolutionary War pension application of Gurdin Burnham dated June 3, 1833 (National Archives, ID #300022, NARA M804, Roll 0420).

[26] Letter from General George Washington to John Augustine Washington dated April 29, 1776 (National Archives); Letter for General George Washington to New York Committee of Safety dated April 17, 1776 (National Archives).

[27] Revolutionary War pension application of Gurdin Burnham dated June 3, 1833 (National Archives, ID #300022, NARA M804, Roll 0420).

[28] Letter from Brigadier General Benedict Arnold to General George Washington dated May 8, 1776 (National Archives).

[29] Letter from Major General John Thomas to General George Washington dated May 8, 1776 (National Archives).

[30] The Writings of George Washington, Volume V (1776), Pages 82-83; Calendar of Historical Manuscripts, Relating to the War of the Revolution, in the Office of the Secretary of State (Albany, New York), Pages 244, 271, 323, 326, & 373; Journals of the Provincial Congress, Provincial Convention, Committee of Safety and Council of Safety of the State of New York, Page 461.

[31] The Writings of George Washington, Volume V (1776), Pages 63 & 83.

[32] Calendar of Historical Manuscripts, Relating to the War of the Revolution, in the Office of the Secretary of State (Albany, New York), Page 314.

[33] Letter from George Washington to John Augustine Washington dated May 31-June 4, 1776 (National Archives).

[34] Letter from General George Washington to Brigadier-General Sullivan dated June 13, 1776 (National Archives).

[35] Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams dated June 26, 1776 (Massachusetts Historical Society).

[36] The Writings of George Washington from Original Manuscript Sources (1745-1799), Volume 5, edited by John C. Fitzpatrick, Page 249; Letter from General George Washington to Governor Trumbull dated July 7, 1776 (National Archives).

[37] Horatio Gates Papers (National Archives); Letter Letter from General George Washington to Brigadier-General Horatio Gates dated July 16, 1776 (National Archives); Letter Letter from General George Washington to Brigadier-General Horatio Gates dated July 29, 1776 (National Archives).

[38] Letter from Major General Horatio Gates to General George Washington dated August 7, 1776 (National Archives).

[39] The Continental Army by Robert K. Wright, Jr, page 287.

[40] Washington’s Crossing by David Hackett Fischer, Page 409.

[41] A History of the Life and Service of Captain Samuel DeWees by Captain Samuel DeWees (compiled by Robert Smith Hanna), Pages 84 & 92-94; The DeWees Family: Genealogical Data, Biographical Facts and Historical Information collected by Mrs. Philip E. LaMunyan, Page 171.

[42] The Writings of George Washington from Original Manuscript Sources (1745-1799), Volume 7, edited by John C. Fitzpatrick, Pages 38-39; Letter from General George Washington to Lieutenant Colonel Robert Hanson Harrison dated January 20, 1777 (National Archives).

[43] Washington’s Crossing by David Hackett Fischer, Pages 352-355.

[44] Alexander Lawson Smith to Lieutenant Michael Gilbert, Maryland Historical Magazine, Volume 5, Pages 131-134.

[45] General George Washington Orders to Doctor John Cochran dated January 20, 1777 (National Archives).

[46] Letter from William Shippen Jr. to General George Washington dated January 25, 1777 (National Archives).

[47] Letter from General George Washington to John Hancock dated January 26, 1776 (National Archives).

[48] Letter from Colonel Mordecai Buckner to General George Washington dated January 25, 1777 (National Archives); The Writings of George Washington from Original Manuscript Sources (1745-1799), Volume 5, edited by John C. Fitzpatrick, Page 122; Revolutionary War Pension Application of Ebenezer Mann S38927.

[49] Letter from George Washington Letter to the President of Congress dated February 5, 1777 (National Archives).

[50] Letter from George Washington Letter to Major General Horatio Gates dated February 5-6, 1777 (National Archives).

[51] Letter from George Washington Letter to William Shippen Jr dated February 6, 1777 (National Archives).

[52] Letter from Governor Trumbull to General George Washington dated February 7, 1777 (National Archives); Letter from George Washington Letter to Governor Jonathan Trumbull Sr. dated February 10, 1777 (National Archives).

[53] Letter from the Continental Congress Medical Committee to General George Washington dated February 13, 1777 (National Archives).

[54] “Smallpox in Washington’s Army: Strategic Implications of the Disease During the American Revolutionary War” by Ann M. Becker, The Journal of Military History (Volume 68, No. 2), Page 424.

[55] Alexander Lawson Smith to Lieutenant Michael Gilbert, Maryland Historical Magazine, Volume 5, Pages 131-134.

[56] Washington’s Crossing by David Hackett Fischer, Page 348.

[57] Letter from Virginia Governor Patrick Henry to General Washington dated March 29, 1777.

[58] Letter from General George Washington to Patrick Henry dated April 13, 1777 (National Archives); The Army Medical Department (1775-1818) by Mary C. Gillett, Page 75.

[59] Report from Lieutenant Colonel James Hendricks to General Washington dated April 12, 1777.

[60] Revolutionary War Rolls (National Archives, ID #602384, NARA M236, Roll 0103).

[61] Muster Roll of Captain Billey Haley Avery’s Company of the 6th Virginia Regiment (National Archives, ID #602384, NARA M246, Roll 0103); Revolutionary War Pension Application of George Blakey W8367; Revolutionary War Pension Application of William Moore S16982.

[62] Revolutionary War Pension Application of William Moore S16982.

[63] The Committee for Foreign Affairs to the American Commissioners dated May 2, 1777 (National Archives).

[64] Letter from General George Washington to Major General Israel Putnam dated June 17, 1777 (National Archives).

[65] The Army Medical Department (1775-1818) by Mary C. Gillett, Page 75.

[66] Smallpox vaccination: an early start of modern medicine in America by Dan Liebowitza.

[67] A History of the Life and Service of Captain Samuel DeWees by Captain Samuel DeWees (compiled by Robert Smith Hanna), Pages 125-126, 138-142. Revolutionary War Pension Application of Samuel DeWees No. W9405 (No. 5263 dated Baltimore County, Maryland).